State of NZ Garden Birds 2021 | Te Āhua o ngā Manu o te Kāri i Aotearoa

What are our birds telling us?

Birds act as backyard barometers – telling us about the health of the environment we live in. They are signalling significant changes in our environment over the last 10 years. We should be listening.

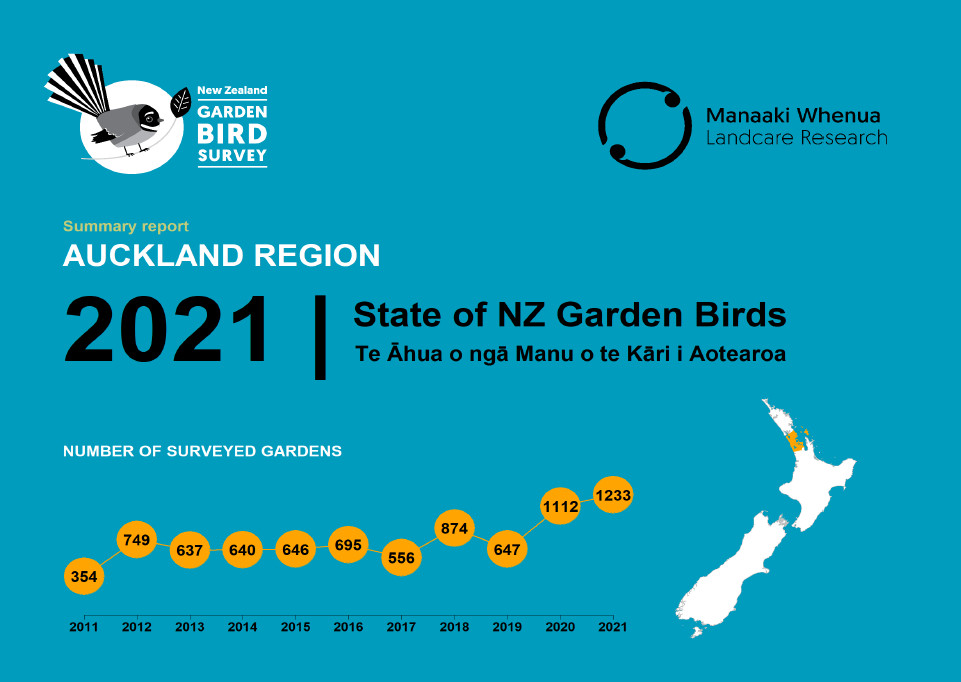

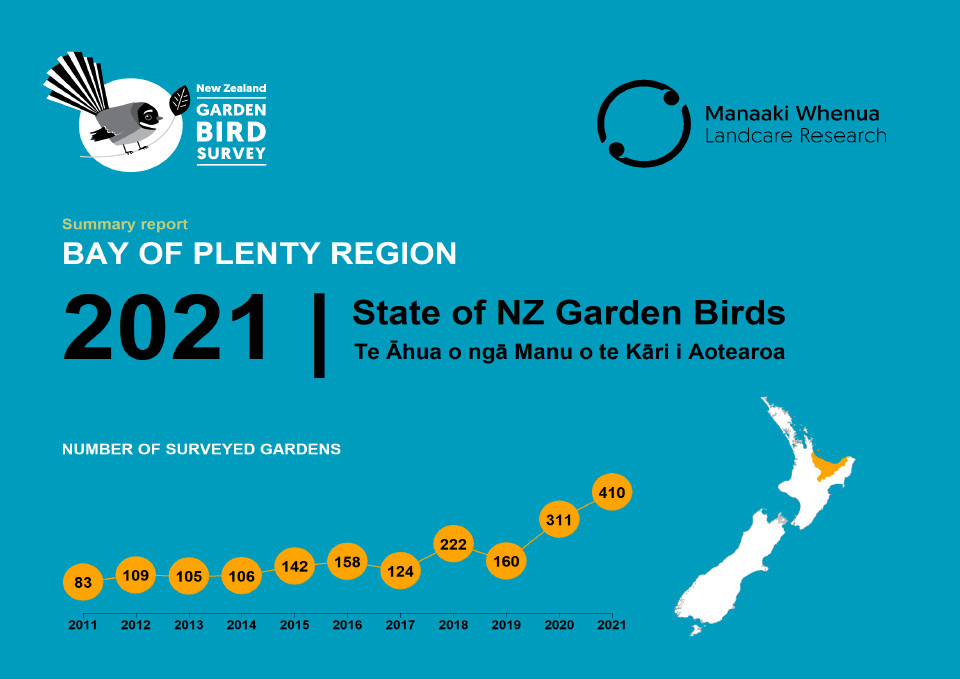

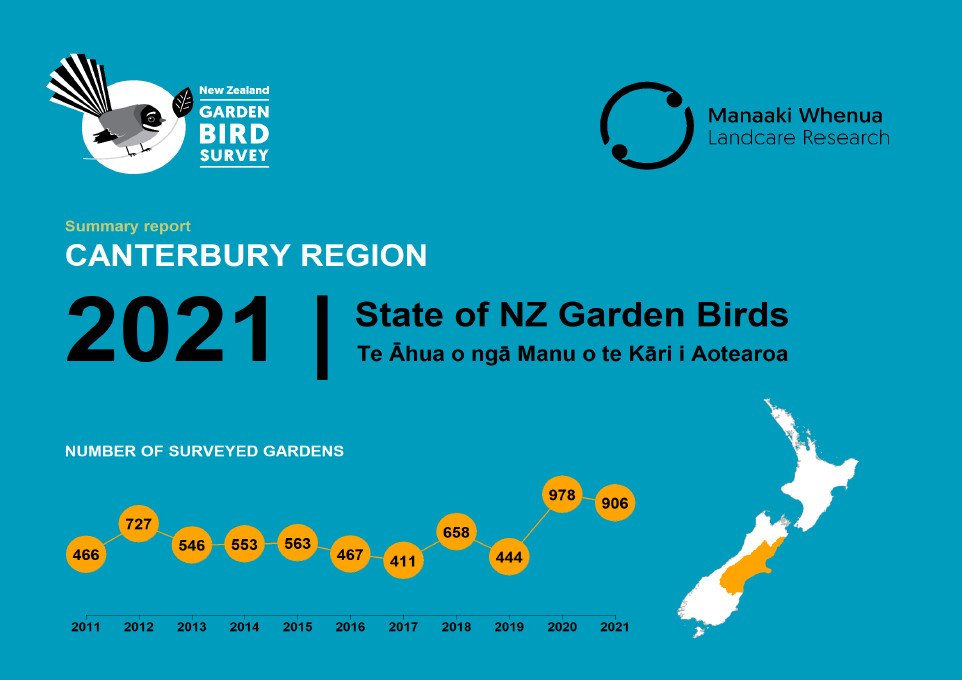

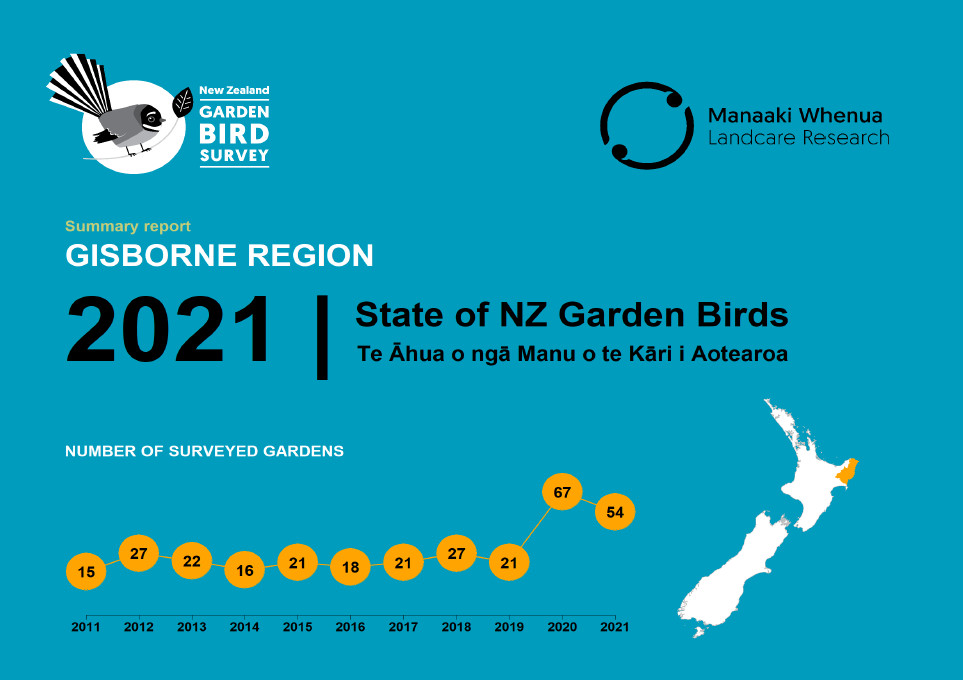

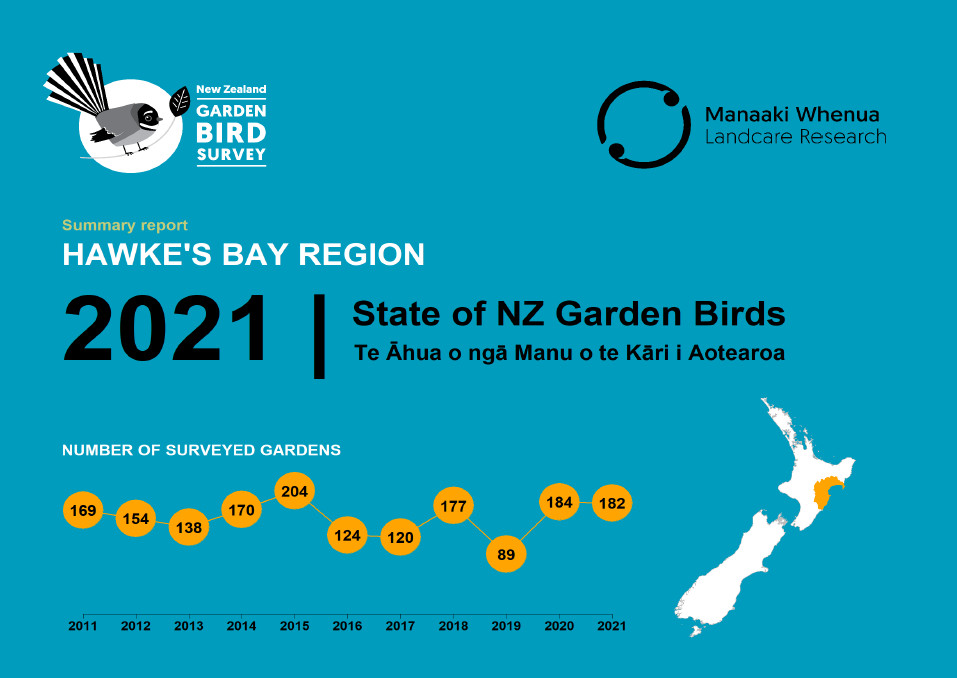

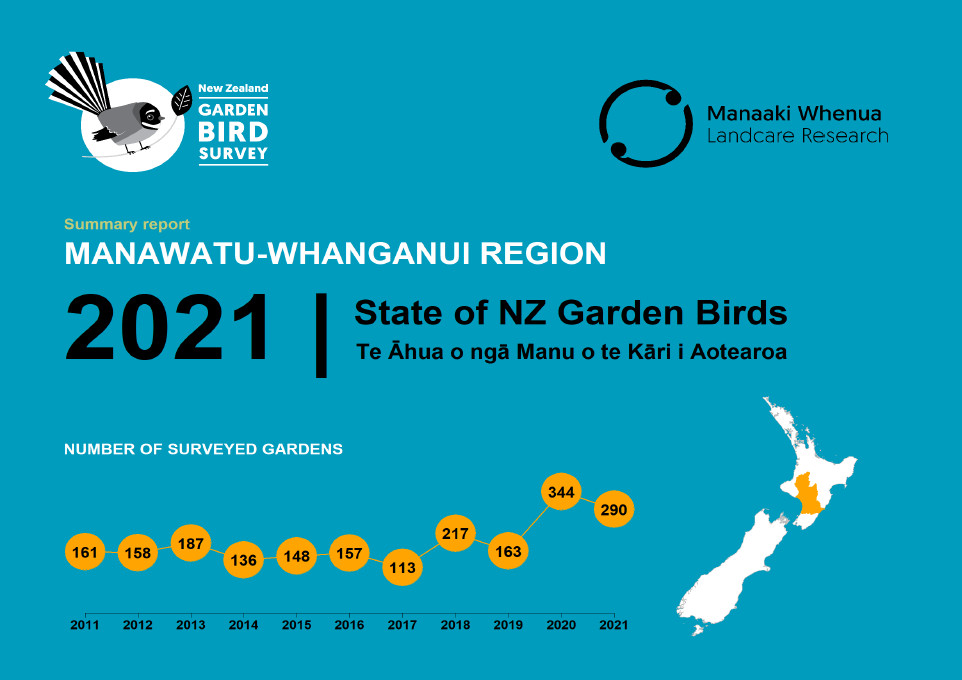

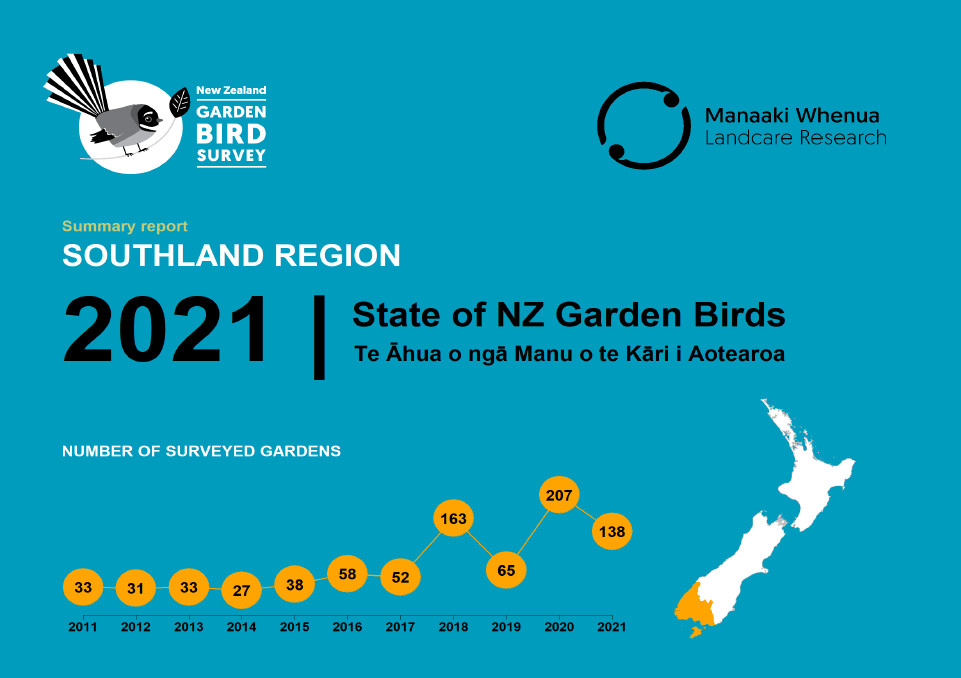

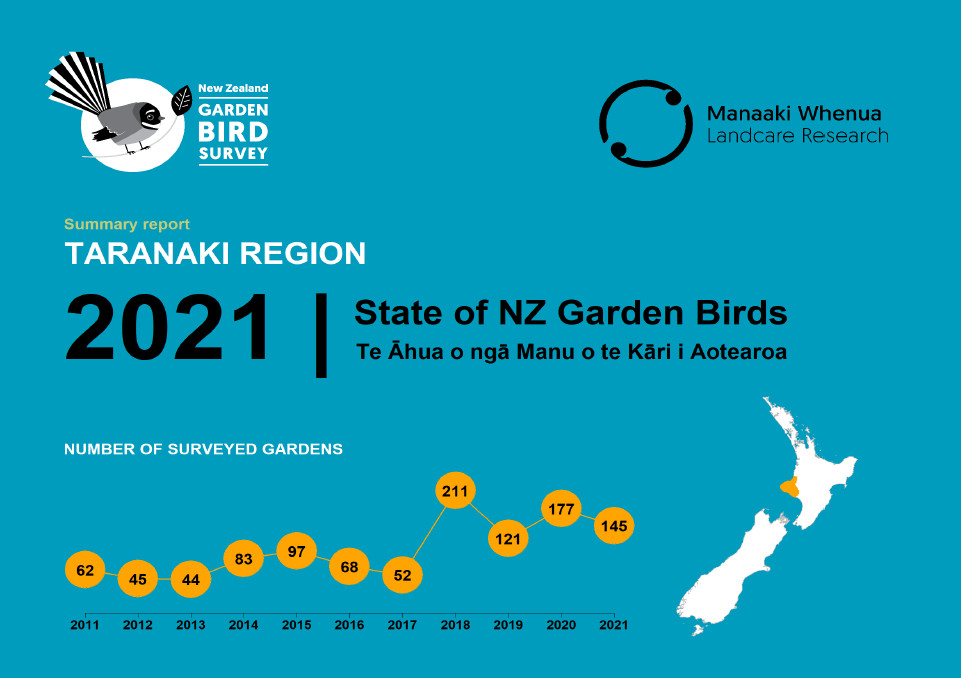

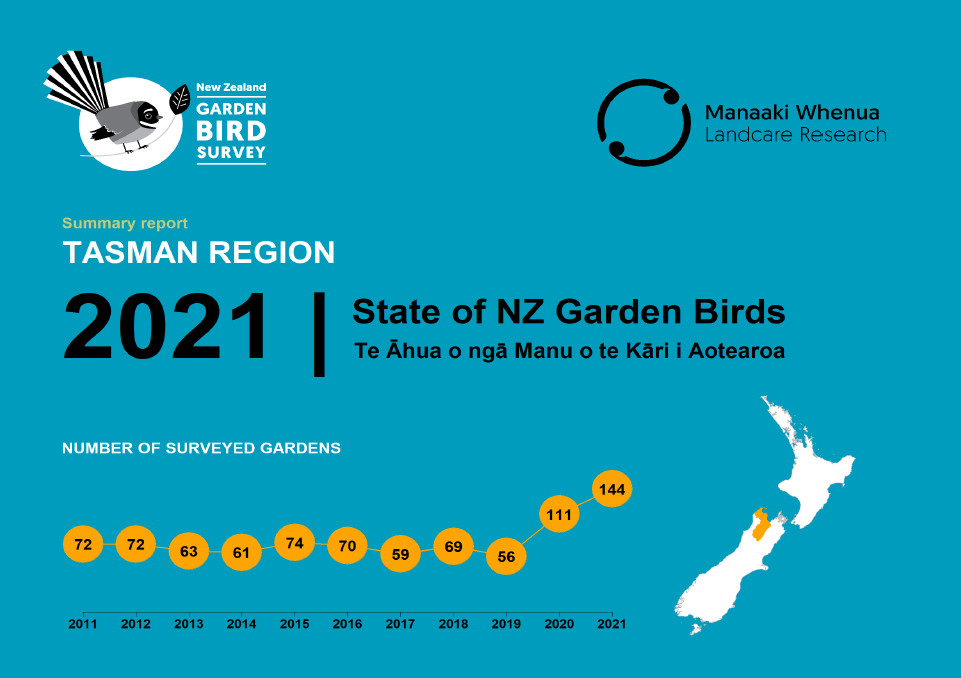

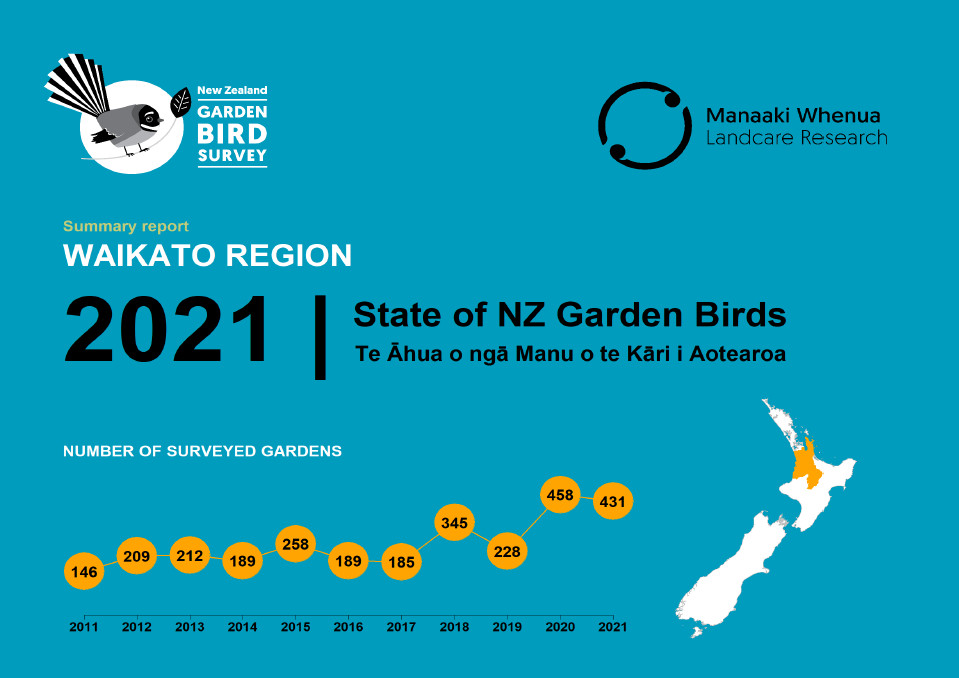

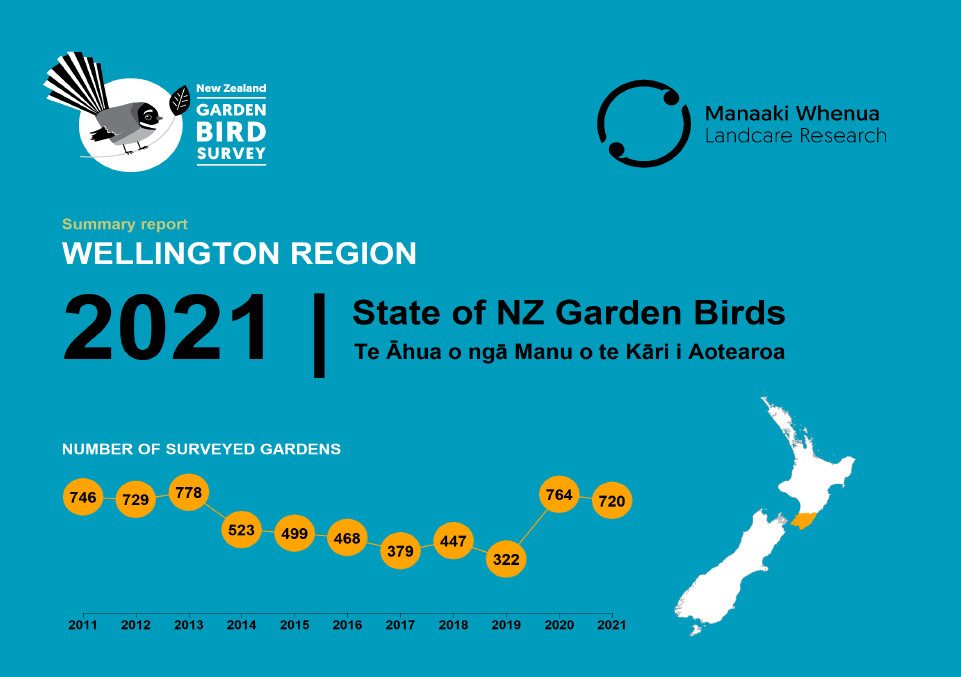

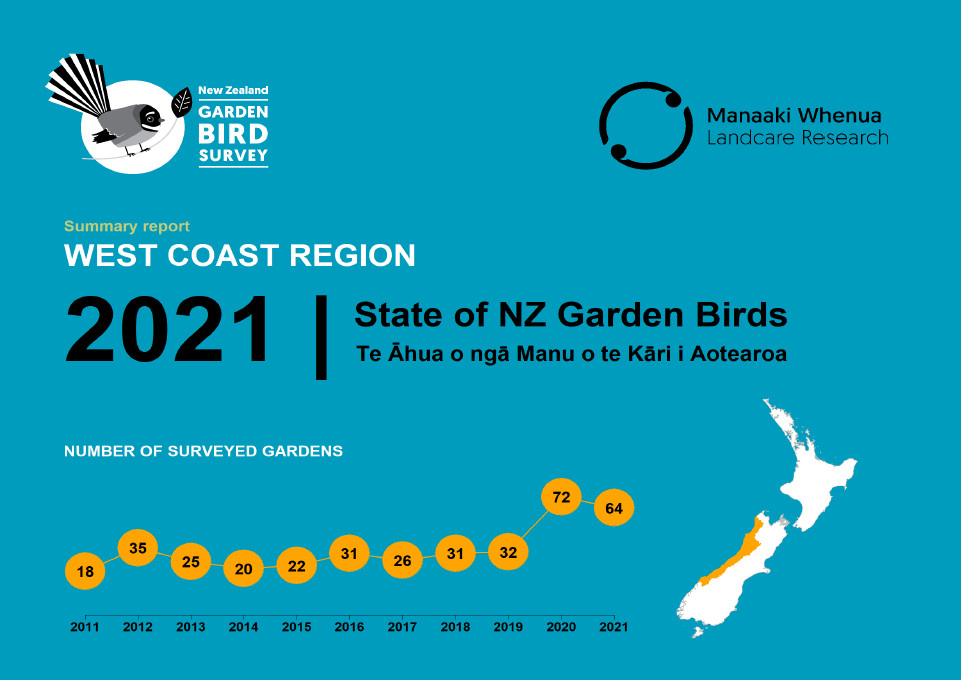

Using cutting−edge techniques, Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research has distilled a substantial information base – bird counts gathered by New Zealanders from almost 42,000 garden surveys since 2010 – into simple but powerful metrics.

Thank you to all the citizen scientists who participated in the survey in 2021. It was a great turnout.

Key findings from the 2021 survey

More good news for four native species:

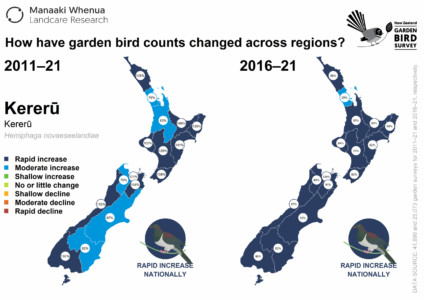

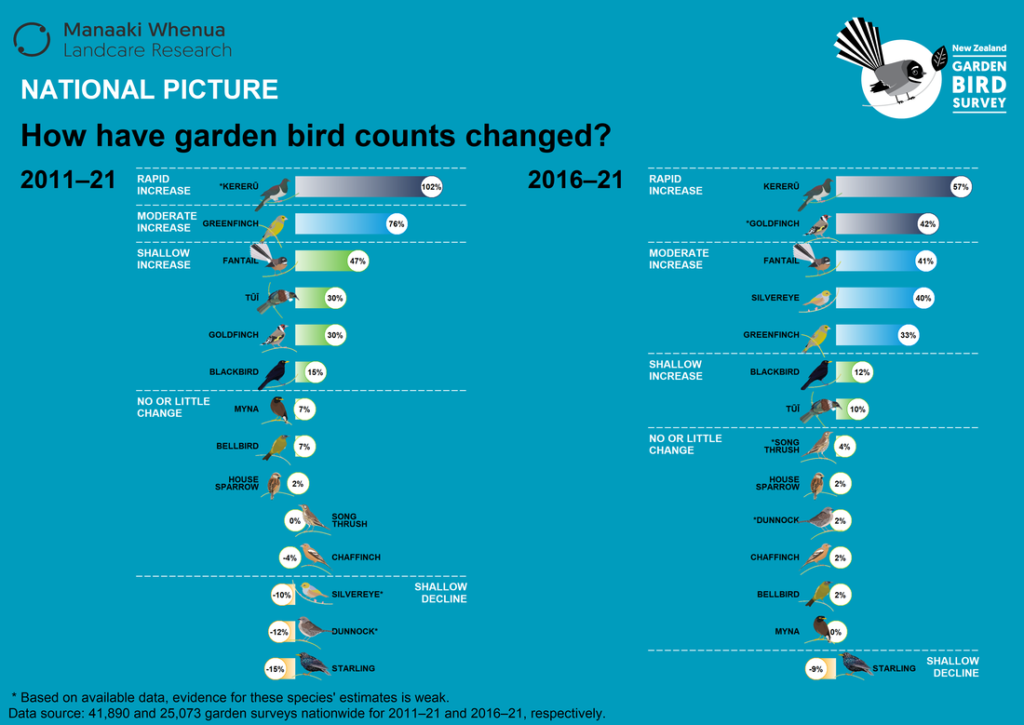

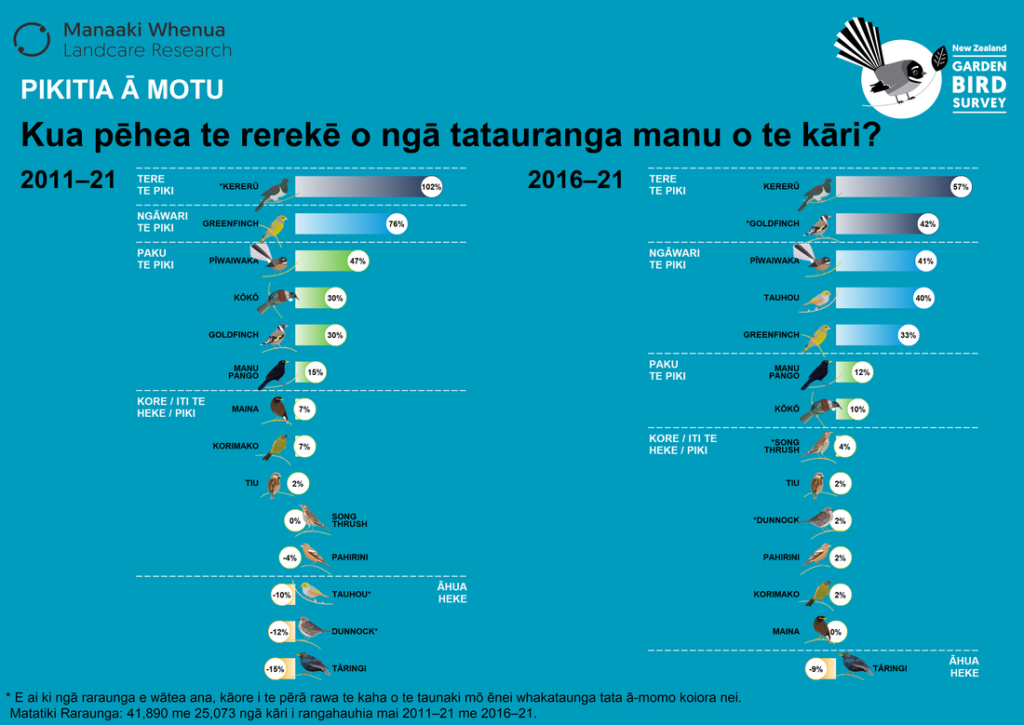

- Kererū counts show a 102% increase over 10 years, increasing rapidly over the last 5 years (57%).

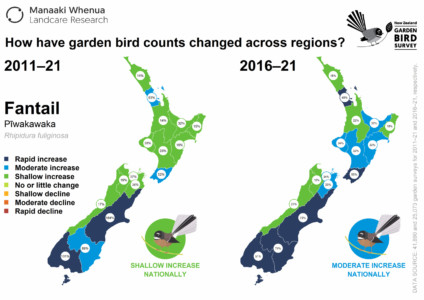

- Pīwakawaka (fantail) counts were up 47% over 10 years.

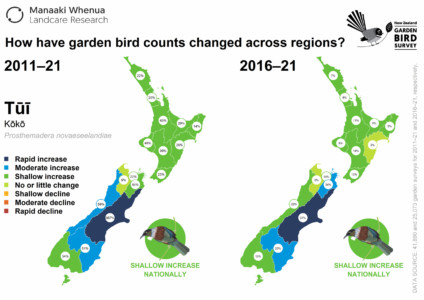

- Tūī (kōkō) continue to increase nationally (30% over 10 years), and increasingly in Canterbury, Marlborough, Otago, and the West Coast.

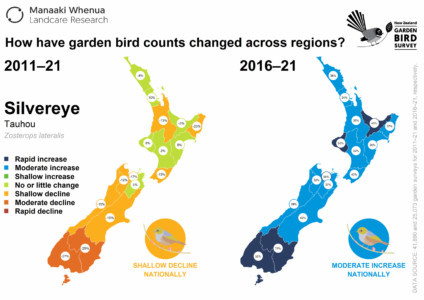

- Silvereye (tauhou) has good news. The data shows its long-term slow decline is lessening (10% compared with 23% last year), with a moderate increase in numbers since 2016.

Introduced species:

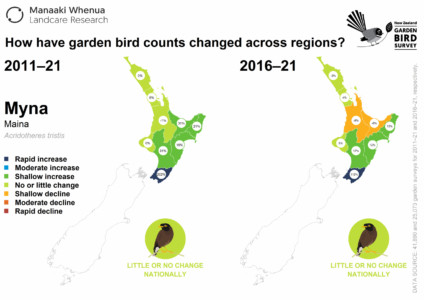

- Myna (maina) There has been little change to counts nationally, but in Wellington they have shown a rapid increase – 202% over the past 10 years.

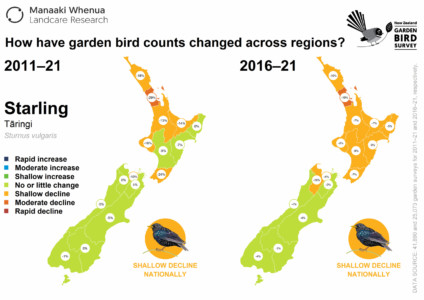

- Starling (tāringi) shows numbers continue to decline over both the five and 10 year period, although their rate of decline has slowed compared to last year.

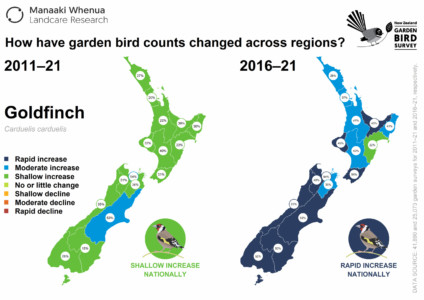

- Goldfinch shows a shallow increase over 10 years that was first detected for goldfinch last year, which has increased (from 18% to 30%).

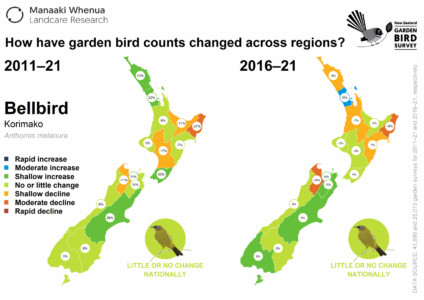

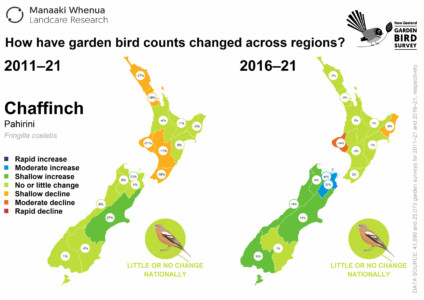

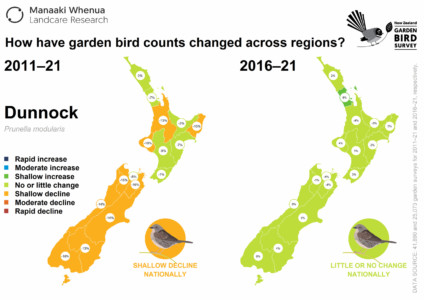

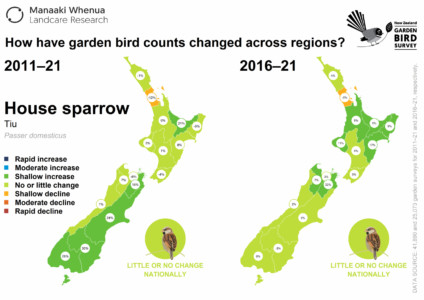

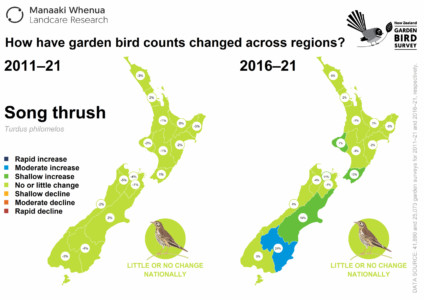

- Numbers of song thrush, house sparrows, dunnock, chaffinch, and korimako (bellbirds) show little change over the past five years.

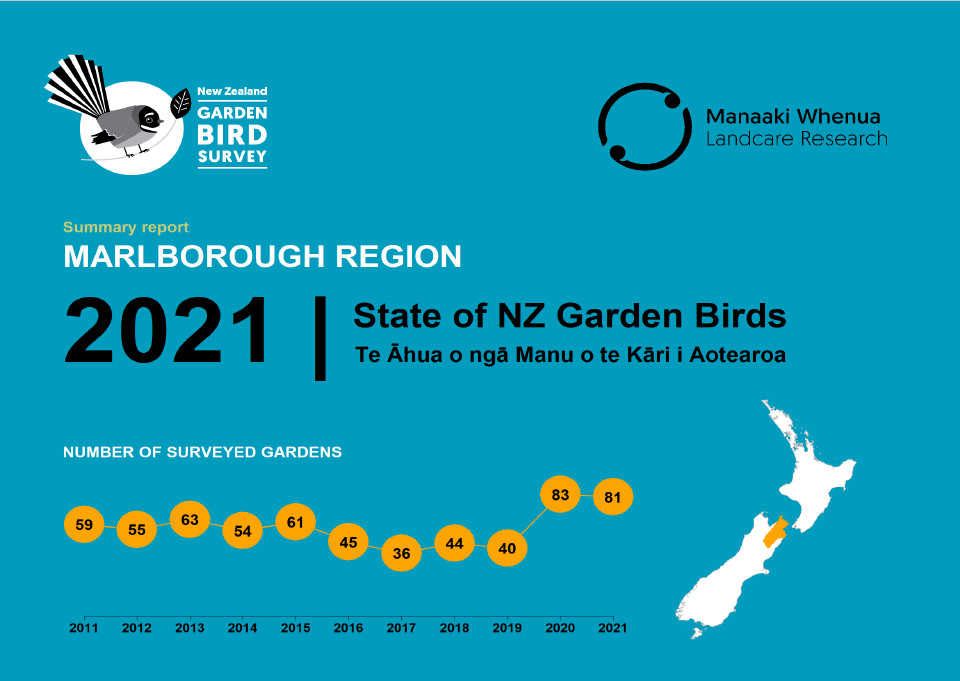

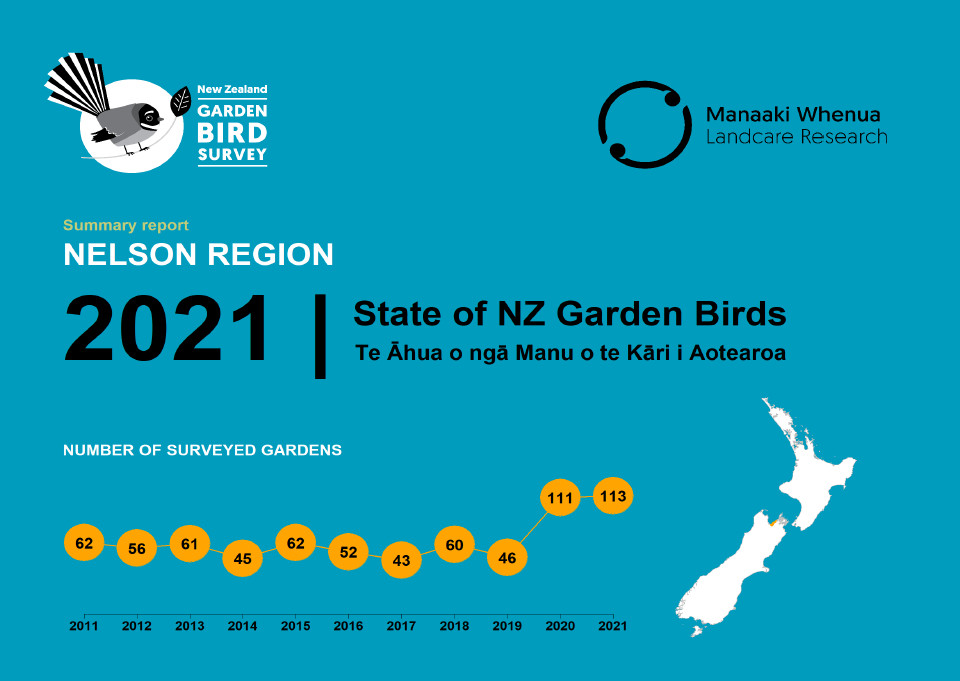

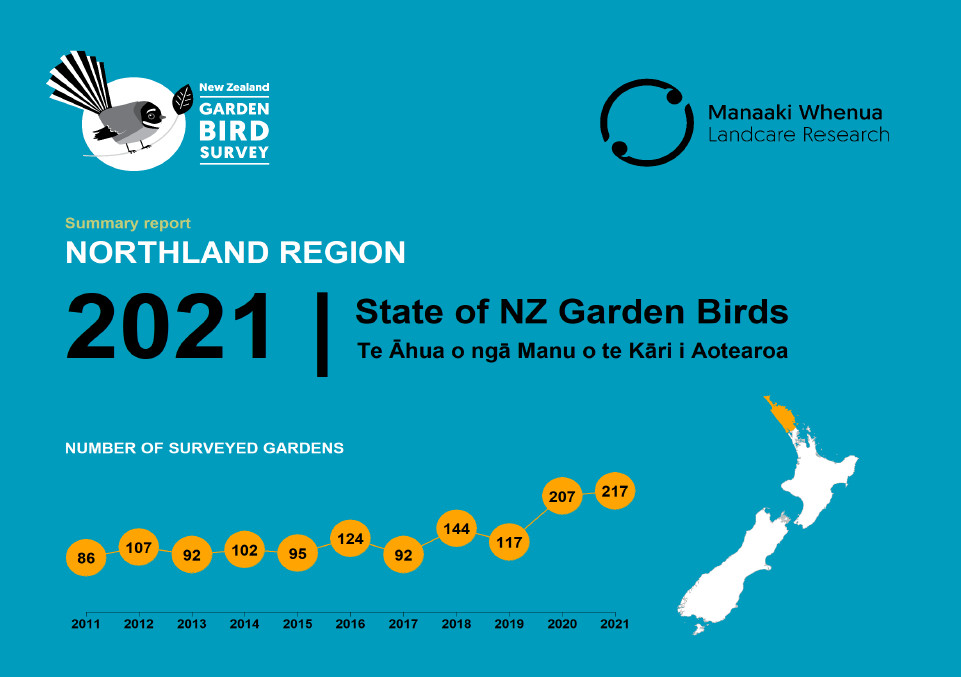

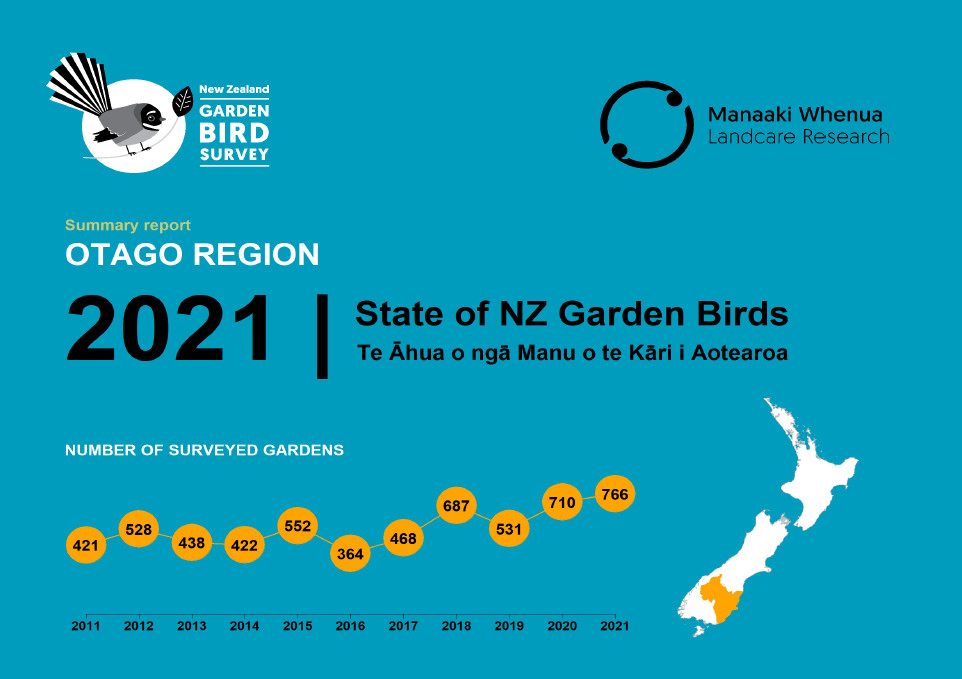

If you’re keen to know more about what’s happening with garden birds in your region, reports for individual regions are available, or check out out the full State of NZ Garden Birds 2021| Te āhua o ngā manu o te kāri i Aotearoa report.

How we calculate NZ Garden Bird Survey results

The general idea behind the survey is to convert the individual bird counts people contribute into meaningful estimates of wider population changes over time. Counts from every garden surveyed are linked to their location within a neighbourhood, suburb, district and region to calculate how bird counts change over time at each of these spatial scales.

We expect a species whose population is increasing over time to show an increase in counts and vice versa. While this is simple in principle, because there are different numbers of gardens in different regions, and different people decide to participate in some years, it might appear as though bird count numbers have changed, when it is just the proportion or location of survey returns that have changed.

Cleaning ‘noisy’ data

The type of garden surveyed (rural or urban), whether people feed birds, and the total number of gardens surveyed in a region also add complexity. Statisticians refer to this as ‘noisy data’ because there are so many variables to take into account.

To reduce this noise, we use cutting edge statistical techniques to account for these variables. Following bootstrap analysis and bias-correction of the modelled data, estimated trends in bird populations over the past 5- and 10-year periods are summarised nationally and regionally according to their direction (decline or increase) and size (rapid to shallow).

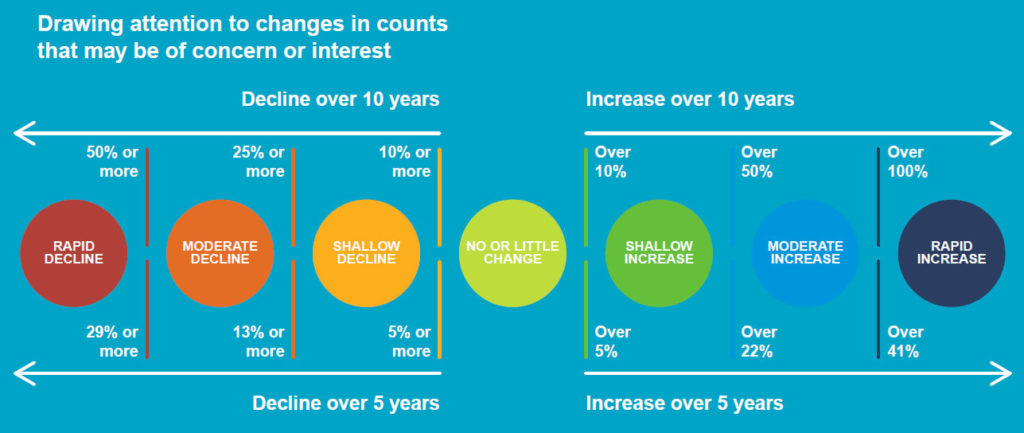

These long-term trends are called ‘signals’ and show a persistent increase or decrease in the abundance of a species. We categorise these signals in the following way:

When using samples to estimate wider populations, we need some way of measuring whether the sample actually reflects the wider population. We used 80% confidence intervals for the average percentage change in each species’ counts to evaluate confidence in our estimates. We generally have more confidence at the regional level than district or suburb.

The easiest way to improve this confidence at the district or suburb level is to increase the number of bird counts done. The more people who participate, the greater the strength of our evidence for what’s happening to garden birds at the local scale.